In this post, my dad, Joe Karrick, writes about wildlife in Bath County. He told me a while back that he didn’t see his first deer until he was a teenager, and that really amazed me. I guess I found that so hard to believe because I take them for granted. I have seen them outside my kitchen window right here in Owingsville. I just never considered that there was a time when they weren’t around, because in earlier days, wasn’t Kentucky known by native and pioneer alike as a land abounding in wildlife? What happened to the deer?

The answer, of course, is that they were over-hunted and their habitat harmed, which consequently led to them being pretty much wiped out. The history behind that and their reintroduction is quite interesting, and I’ve included a link to the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife’s page on the history of deer management in Kentucky, where a timeline is shown starting with Thomas Walker’s observation in 1750 that deer were “plentiful.”

Yes, deer were plentiful but by just 1775, the Virginia Legislature was attempting to address the diminishing deer population, and by 1810, James Audubon wrote the once plentiful deer had “ceased to exist.” In 1916, deer hunting was banned in Kentucky.

Deer were overhunted but it’s important to not vilify outdoorsmen. Good hunters care about healthy animal populations as much as anyone else, and there have always been those voices of reason. For example, Daniel Boone, that mighty frontiersman himself, is considered to be the first “game warden” in our state after he was appointed to oversee Boonesborough’s “game committee.” I don’t hunt and I eat very little meat, but I appreciate hunters who act as stewards of our beautiful land and its creatures. They are some of the very best advocates for game laws and regulations because they know what can happen otherwise.

From my dad, Joe Karrick:

As a boy growing up in Bath County, Kentucky, during the 1950s, I spend a lot of time in the fields and woods. I pretty well knew what animals were in the woods. There were no deer until the late 1950s, no turkeys, no coyotes, no eagles, no elk, and no bears.

Deer were hunted to near extinction by the start of the 20th century. The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife did a lot of restocking of deer across the state. I started seeing deer in the woods after about 1957. Today’s deer population in Kentucky is about one million.

Turkeys were restocked starting in 1978. I often see turkeys now like the mother and her chicks in the summer on my farm.

I saw no coyotes in the 1950s. Most folks think that coyotes came into Kentucky in 1977-78 when the Ohio and Mississippi rivers froze over and they coyotes walked across them into Kentucky from neighboring states. Coyotes are everywhere in Kentucky now and can be a pest. I grow sweet corn for market – coyotes eat sweet corn!

I never did see a bear in the 1950s, but I did see a track in the mud in the Clear Creek area. Bears have expanded into Kentucky from the east. Kentucky habitats have improved. Forests that regenerated after the heavy wholesale logging in the early 20th century are now mature and are providing heavy crops of nuts, acorns, etc., which the bears love. Bears are now sighted every year in Bath County.

I did not see any eagles in the 1950s. In the last few years, I have seen eagles, even had one fly over my house!

Eastern elk were hunted to extinction in Kentucky by 1860 or so. The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife have introduced western elk into strip mined lands in eastern Kentucky, and the population now is about 18,000.

I have never seen a mountain lion here in Bath County. There have been confirmed sightings in Tennessee and Missouri, and sightings are increasing.

A cougar was killed in Bourbon County in 2014 by law enforcement. It is believed it was a pet that had escaped. My sister, Janet, lived the Clear Creek area and while driving in the National Forest one afternoon late, she swore she saw a large tan, long tailed cat with two cubs. Sounds like a cougar to me!

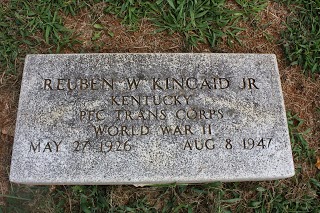

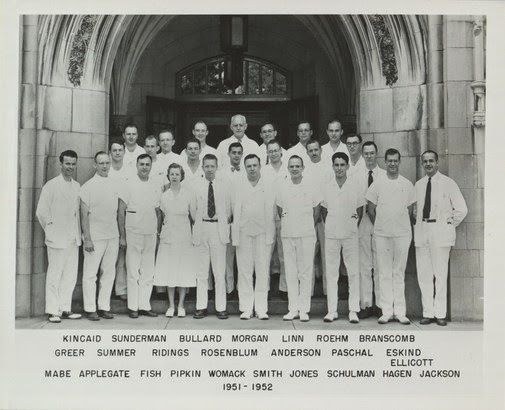

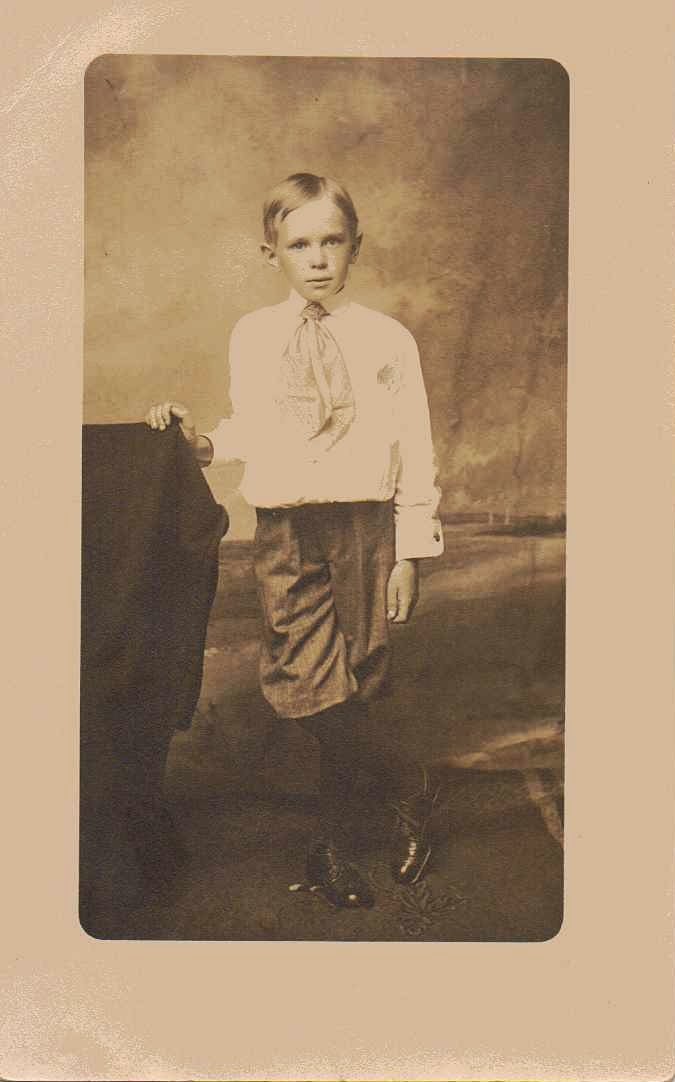

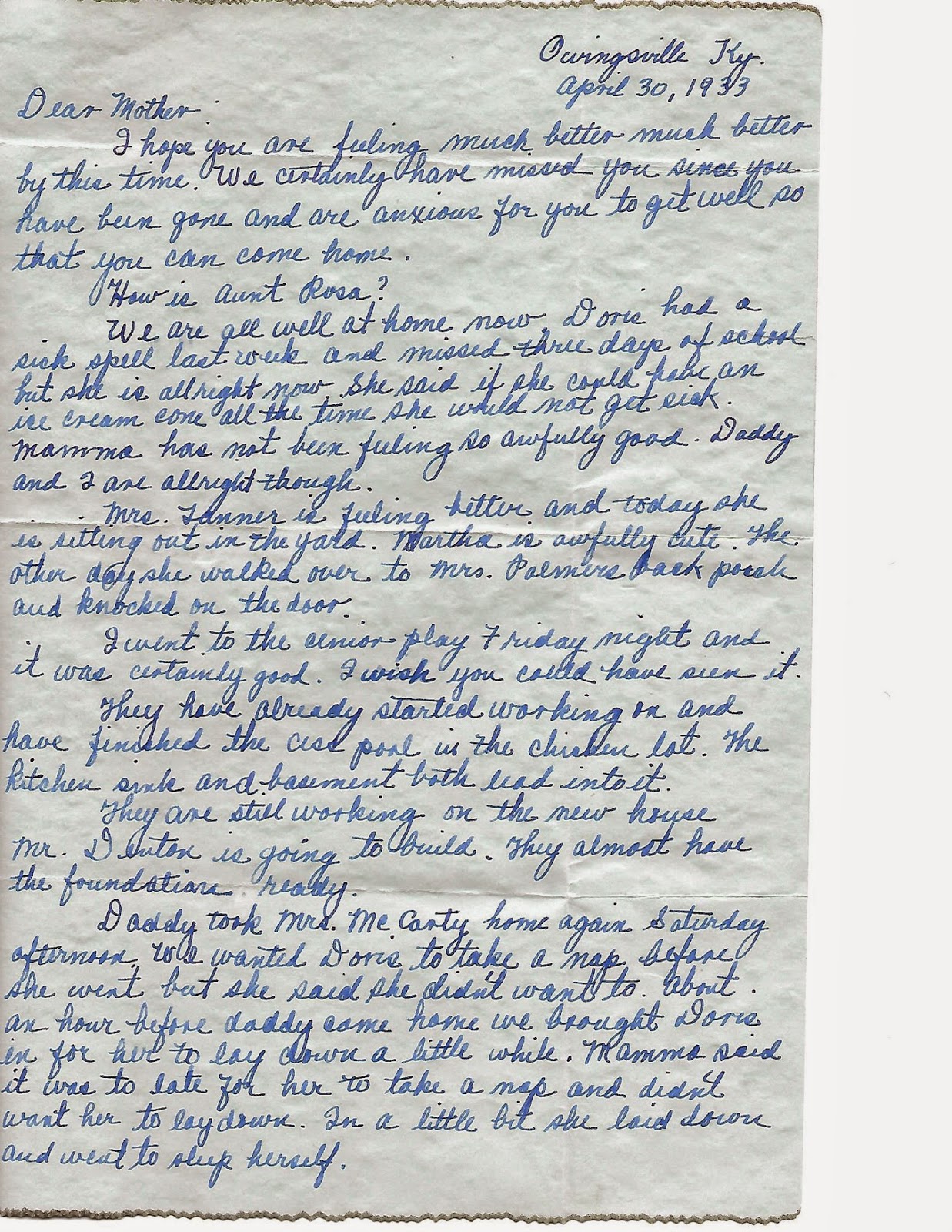

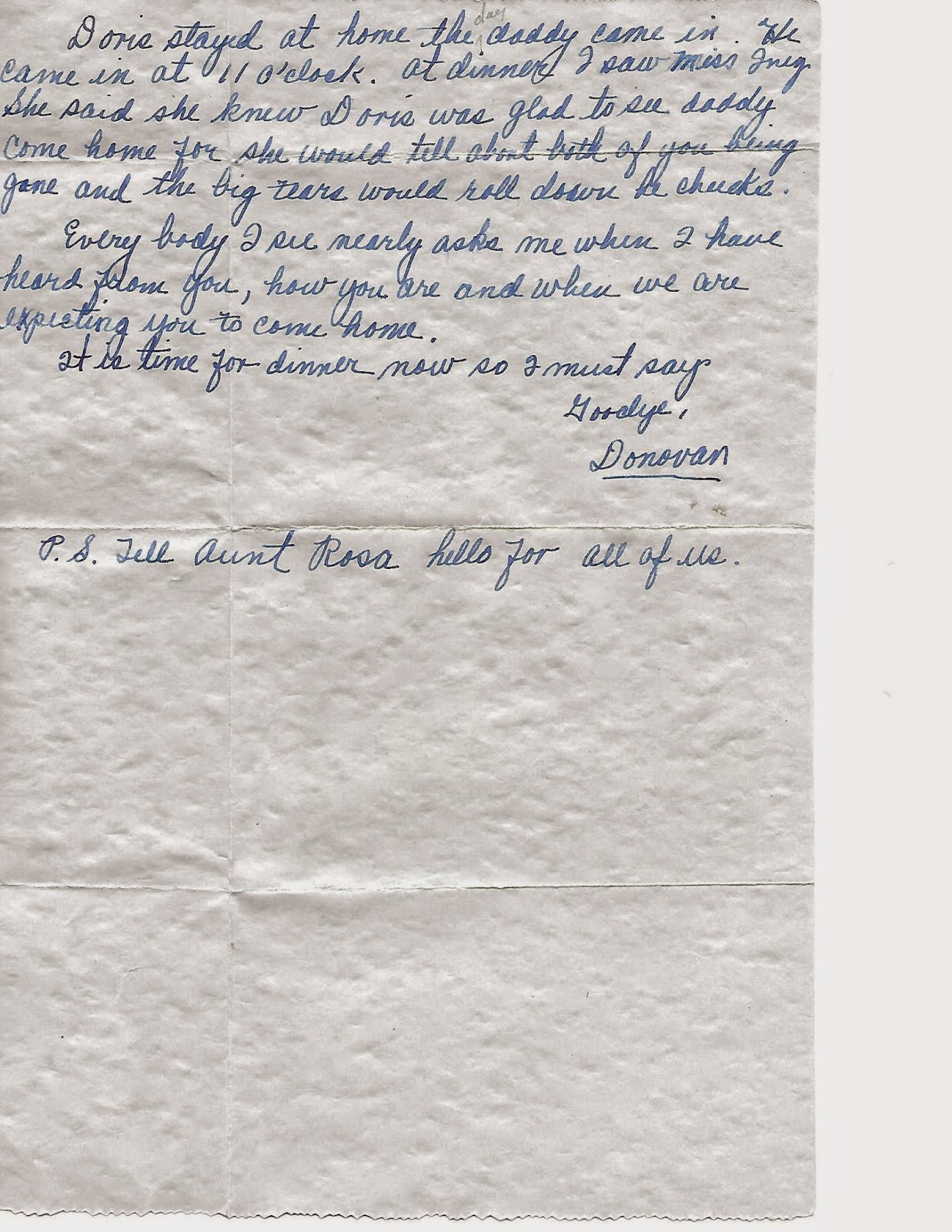

Dad writes about cougars, and Don’s father, Burl Kincaid, Jr., wrote about them, too, but he called them “catamounts.” His grandfather, Jacob Kincaid, told the story of the “Catamount Hunt of Stepstone” and you can read about that here: https://journalsofwilliamburlkincaid.blog/2014/01/09/the-catamount-hunt-of-stepstone/

Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife’s history of deer management: https://fw.ky.gov/Hunt/Pages/History-of-KY-Deer-Management.aspx#:~:text=So%20the%20Kentucky%20Division%20of,Crittenden%2C%20Livingston%20and%20Ballard%20counties.