-

Mary Pillow Dawson Ficklin – my chance discovery.

My late husband’s parents kept everything. I mean generations of family pictures, many of them still in frames. Recently, I decided to take one of the pictures out of its frame… Continue reading

-

Dawson Headstones

I’ll try to add more info to this post in the future. Continue reading

-

What’s in the Woods? – My dad’s memories of growing up without deer, turkey, bear, and elk in Salt Lick, KY.

In this post, my dad, Joe Karrick, writes about wildlife in Bath County. He told me a while back that he didn’t see his first deer until he was a teenager,… Continue reading

-

My dad’s memories of stripping tobacco on the family farm in Salt Lick, Ky.

In this post, my dad, Joe Karrick, reflects on his memories of stripping tobacco. As he notes, tobacco was once grown on almost every Kentucky farm. Indeed, data from the USDA… Continue reading

-

Hog Killin’ Weather

-

A post to honor my late husband.

As people in my community and circle know, my husband, Don Kincaid, died on June 18th of this year after a long and often brutal battle against liver disease caused by… Continue reading

-

"Cap" Dawson’s Blacksmith Shop

In this entry, Mr. Burl writes about the blacksmith shops that were in Owingsville and specifically mentions “Cap” Dawson. In his book, The History of Bath County, John Adair Richards also… Continue reading

-

Christmases Past

From the journals of Burl Kincaid: In the early 1900’s, most Christmas shopping was done locally and from Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogs. There was very little traveling to… Continue reading

-

Fratman Hall

There used to be a place in Owingsville where actors would gather and put on grand performances. Seriously. From the journals: “Chick” is in there selling nuts and bolts, paints… Continue reading

- Black History

- Brother

- Cemeteries/Headstones

- Craycraft

- Darnell

- Dawson

- Entertainment

- Ficklin

- Genealogy/Surnames

- Goodpaster

- Karrick

- Kincaid

- Military History

- Miss Jane's Letters

- Mr. Burl's Writing

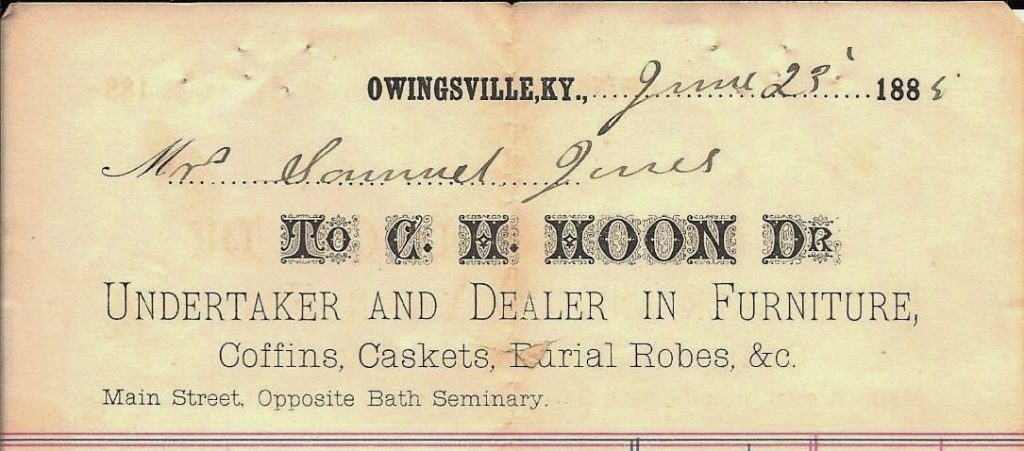

- Old Funeral Notices

- Old Pictures

- Owingsville

- Recipes

- Salt Lick

- Thompson

- Uncategorized

Hi, I’m Ginger Kincaid, and I manage this blog. I hope you find things of interest here, and please reach out if you have any queries. I’m not super active on here, but will add new things from time to time, mainly genealogy related content. My current surnames of interest are Ficklin, Dawson, and Young, especially how they relate to the Confederacy. I’m also researching the early organization of the Daughters of the Confederacy in Owingsville. I am not pro-Confederacy, but apparently some ancestors were.

Pictured with my late husband, Don Lee Kincaid, who was simply the best.